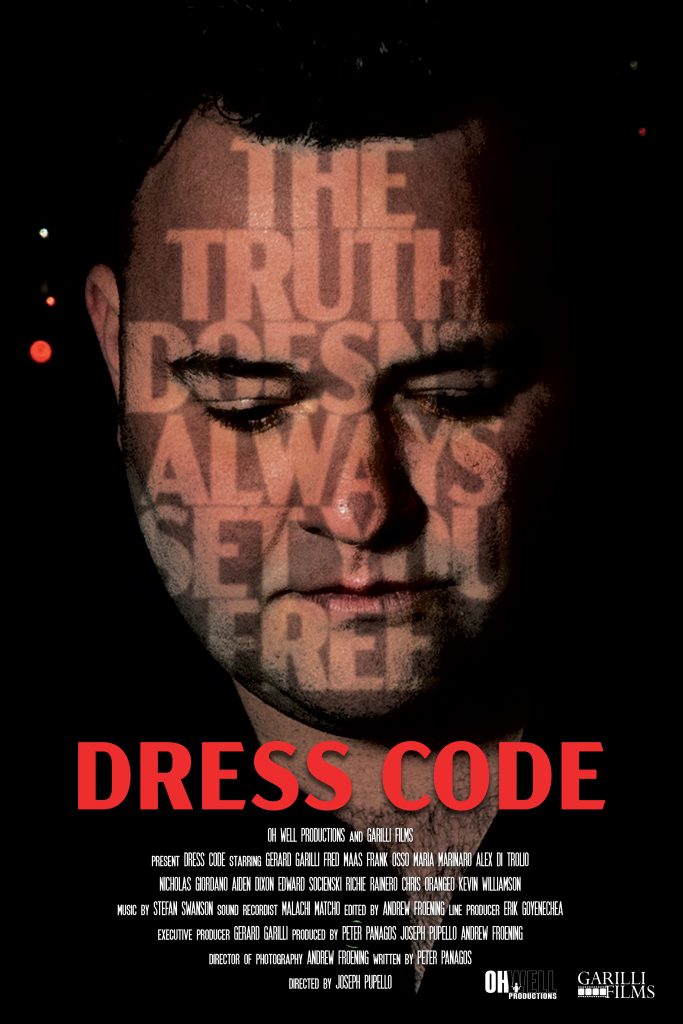

Born into a life of organized crime, Bobby Russo lives a life of secrets and lies. As he gets older he realizes that the most dangerous secrets of all, are his own in the mafia drama Dress Code.

“As far back as I can remember I always wanted to be a gangster.” These are the words spoken by Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill during the opening of Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece Goodfellas, in my opinion, the greatest film ever made about organized crime and I include The Godfather in that comparison. The majority of Scorsese’s best films have always been about guilt and Joseph Pupello’s Dress Code, like Goodfellas, is about guilt more than anything else. But it is not as straightforward as establishing the good and then guilt is the result of committing the crimes. No, the ‘hero’ of this film feels guilty for not being true to himself and for being born with certain feelings and thoughts that his dad, a local Mafioso, his friends, and his God, would be absolutely disgusted by. Bobby’s punishment for this is to become so embroiled in this hostile environment that he has to painstakingly live a complete lie in order to survive it.

Gerald Garilli plays Bobby Russo, who we first see in flashbacks. His dad is a violent criminal who subjects young Bobby to beatings and verbal abuse. Very early in the film, we learn that Bobby is struggling with his sexuality and that he is more comfortable dressing in women’s clothing – behavior that is so frowned upon in the tight-nit, gangster, and catholic community he lives in, that it could actually get him killed. As a result, Bobby hides this aspect of his personality and as we flash forward 10 years we find he has risen steadily through the wise guy ranks. carrying his potentially deadly secret with him. The movie will flash back and forward to young Bobby and old Bobby throughout its 108-minute run time.

Dress Code’s screenplay, written by Peter Panagos, sometimes feels like a therapy session; it contains a lot of psychological theories about Bobby’s mental state but it also tells us things about the lower ranks of organised crime gangs, how people start out as debt collectors, hired muscle, or thugs who ask questions and then point guns in people’s faces, even after they get their answers. There is no glitz or glamour in this gangster film, it’s all petty, gritty, and dull with low-level crimes taking centre stage, but that is also why it stands out. When Bobby finally succumbs to his real feelings and he visits a local bar, it creates a bright uplifting feeling in the audience and we realise that both director and writer have a huge amount of enthusiasm for their material.

Andrew Froening’s cinematography creates an insular claustrophobic feeling that insists the mob world, even in this day and age, is still a real thing. Sometimes the camera follows Bobby, but at other times it represents different people’s points of view. We’ll see Bobby talking to others, like the flashback conversations with his mother, and scenes with his girlfriend and father. During some of these scenes, Froening rarely allows his camera to be still, the over-the-shoulder reaction shots and two shots that we see seem to be always moving a little, and a moving camera stops us from being a fly on the wall and gets us actively involved in the conversations.

Despite its regular reliance on gangster cliché, Dress Code has at its centre a very modern-day and original story that will not only spark conversation during the film itself but long after it finishes as well.

Leave a Reply